December 1990: Rising leg spinner Shane Warne was making his debut with the Victorian second XI against Western Australia in a mid-week trial at the Albert Ground. Among the opposition from the Golden West were multi-gifted trio Justin Langer, Damien Martyn and Stuart MacGill, all destined for Test cricket.

Only a few spectators had drifted in, most from nearby offices.

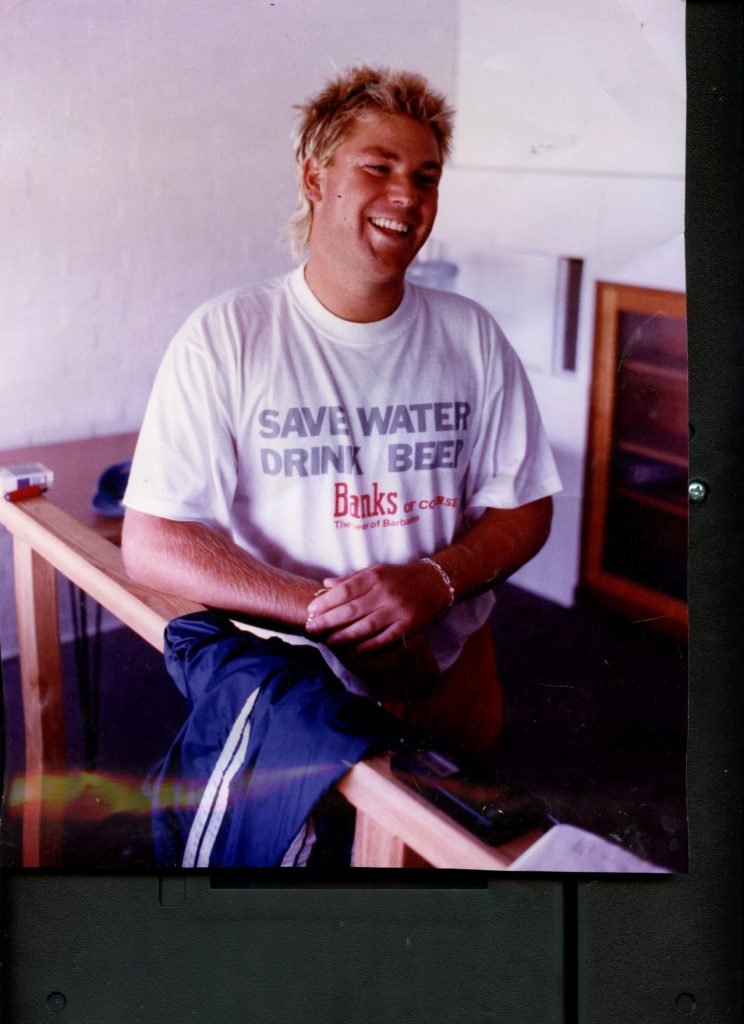

Lunch was called and instead of walking off with his new teammates, Warne readily agreed to my request to be photographed, close-up, by our Sunday Press snapper.

He bowled two or three deliveries to me, standing over the opposite stumps at the Fitzroy St. end. They dipped, curled, hummed and scuttled sideways at pace, reddening my hands.

Even then he had the leg-break from heaven.

He was warm, friendly and endearing. Within weeks he was playing for Victoria and just over a year later, for Australia.

His surge from Brighton’s second XI had been stunning.

At his very first club session at St Kilda, coach Shaun Graf asked the club’s practice captain Noel Harbourd what the 17-year-old with the long blond hair said he did. ‘He told me he was a batsman who also bowled a bit,’ said Harbourd.

‘Not sure about his batting,’ said Graf, ‘but he sure can bowl.’

No one had any idea that he was to become as inspirational to millions worldwide as Don Bradman, the eighth wonder of the world.

David Hookes once asked Warnie at one wintertime pre-season session how many days, or weeks, it took for him before he felt like he was back in full flow. ‘About 20, maybe 21 balls,’ said Shane. He was a captivating, uninhibited, enigmatic, once-in-a-lifetime genius, who revived a lost art and inspired millions globally to love and follow cricket.

Warnie triggered more Australian Test wins than even The Don. He was a rock star in creams: captivating, charismatic, caring, empathetic and incredibly loyal and generous.

Australia had not had a more outstanding or magnetic sportsman since 1950s pin-up boy Keith Miller.

The grief felt on Shane’s death, aged just 52, on that early-autumn weekend was universal. Tens of thousands attended his MCG farewell. We were united in tears.

Like the deaths of JFK and John Lennon, we all could remember exactly where we were on hearing the news. Shane’s heart had stopped. We all wore black armbands that Saturday at Mt. Eliza CC. The atmosphere was eerie. I told the young ones in our team how extraordinarily gifted Shane was – and how relentlessly he’d worked to perfect his skills. Asked once how many hours he’d taken to fine-tune his game, he said, ‘10,000… minimum’.

Warnie lived life to the fullest and had friends across every spectrum and sector. From first carting beds to pay for his fags and fast food, to owning some of the most expensive and desirable real estate in Melbourne and beyond, his life was a scriptwriter’s dream, full of extraordinary highs and eccentricities. We forgave his foibles and follies and years after his retirement, all smiled at his high-rolling ways and hung on his every word from commentary boxes around the world.

Few had as firm a handshake, wide smile or zest for life. He was ‘The King’, cricket’s consummate bowler and showman, whose appeal transcended sport. Millions worldwide still can’t believe he has gone.

His parents Keith and Brigitte were so stunned, they said they would never come to terms with their son’s premature passing. His daughter Summer said she wished she could have hugged her father tighter in ‘what I didn’t know were my final moments with you’.

‘And your final breaths were only moments away.’

Son Jackson said he wished it was just a horrible nightmare and that his Dad would again roll through the front door, armed with pizzas and say ‘who’s hungry?’

During his halcyon playing days and fairytale ride in the ‘90s and early ‘00s, I wrote three Warnie books and he contributed forewords to two of mine, including the life story of his coach, another knockabout larrikin, Terry Jenner, who’d spent time in the Big House.

They’d been introduced while Jenner was out on parole. ‘TJ’ was immediately taken by Shane’s firm handshake and warm, genuine smile.

‘Show me what you’ve got son,’ Jenner said as they trudged down to a side net at the Adelaide No. 2.

Without any ceremony and still in casual clothes, Warnie produced one of his signature leg breaks which spun a foot and bit into Jenner’s hands. ‘Gees @#$% Christ,’ said Jenner to himself.

Throwing the ball back to Warnie, he called: ‘Must have hit a stone son. Try another.’

He did and the second one spun even further.

‘That’s enough for today, son,’ he said.

Jenner was to become his long-time coach and mentor and helped fashion his deadly flipper first taught to him by Jack Potter at the Cricket Academy in Adelaide.

One of Jenner’s proudest moments was witnessing the Warne flipper which castled the champion West Indian Richie Richardson and triggered Australia’s win in Melbourne’s Christmas Test in 1992.

When first introduced to the flipper, Warne couldn’t initially control it. ‘The square leg umpire would have been in danger, so wide did Warnie bowl it,’ said Potter. ‘Yet within days, having practiced incessantly with a tennis ball down a corridor, he’d mastered it. He had an extraordinary gift.’

The Richardson dismissal, which won a hometown Test, was the precursor to the ‘Ball of the Century’, the delicious leg break which spun drunkenly to hit Mike Gatting’s off stump in the opening 1993 Ashes Test at Old Trafford. Gatt’s bewildered shake of the head was the precursor for years of unrelenting Warne bullying on every English XI he encountered in the next 15 years. No one competed as hard, were as driven or so excelled in the biggest matches.

Even in 2005, when England won the greatest Ashes series of the modern era, Warne took 40 wickets – and at a time when his life around him was crumbling.

Warnie was to finish with 700-plus Test wickets. ‘And they were pure wickets too,’ said Jenner proudly. He’d always been unimpressed by the validity of the action of bent-armed Sri Lankan spinner Muthiah Muralidaran. ‘The rules were changed to keep Murali in the game,’ said Jenner.

Off the field Warnie’s life was one roller-coasting soap opera, full of riveting twists and turns.

He led a Peter Pan-type lifestyle, partying hard and often with multitudes of pretty women. From playing the harmonica on stage one night in Melbourne with his mates from Coldplay to high-level poker, celebrity golf at the Albert Dunhill, coaching, mentoring and philanthropy, his influence was multi-tiered. He was even engaged for a time to high-profile Hollywood actress Liz Hurley.

When his Foundation was exposed – it had been donating less than 30 per cent of proceeds to the charities it supported – it was said he donated the last $400,000 in the fund to one unfortunate child who had suffered a life-threatening injury.

He was truly larger-than-life, a man for the people, idolized everywhere. The Don may always be cricket’s No.1 name, but Warnie is its ultimate celebrity.

-Ken Piesse